Show up

We have a burning desire to contribute, collaborate and add value - taking pride in everything we do. We take initiative, are prepared, and are accountable. We show up.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

We have a burning desire to contribute, collaborate and add value - taking pride in everything we do. We take initiative, are prepared, and are accountable. We show up.

By understanding our clients’ businesses, values, and needs, and having industry-leading expertise, we deliver high quality value-adding solutions and maintain strong relationships. We build trust.

Each of us recognises the people we interact with as individuals and treat each other fairly. We are empathetic, and seek to understand each other, our experiences and our diversity. We see each person’s unique talents and inherent value.

We are wired to learn, grow and continuously improve. We take responsibility for a growth mindset and seek challenges. We evolve and thrive through discovering new ideas.

As active citizens we show that transformation drives growth and shifts the dial in our workplace and nation. We remove obstacles and create opportunities for black people to participate meaningfully in building an inclusive economy. We have the courage to be agents of change through walking the talk and getting transformation right.

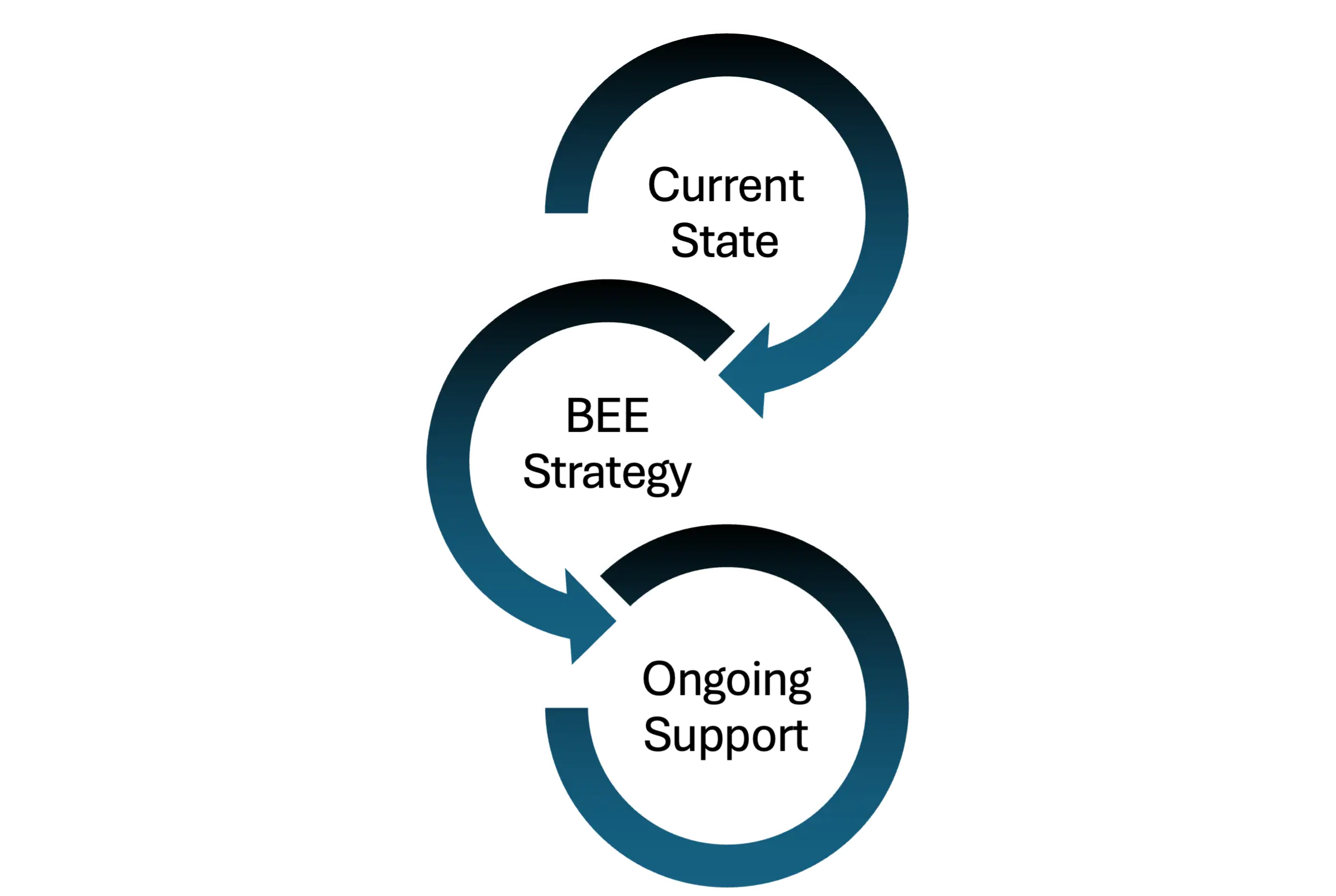

Our process:

Bcom, CFA, MBA (Manchester)

Bruce is the Managing Director at Transcend Capital. He has 12 years of experience in structuring multinational BEE transactions which include Black operational partners, employee, Broad-based Ownership Schemes and the sale of assets to Black investors. Prior to joining Transcend Capital, Bruce was a trader and structured finance professional at Investec Bank.

Transcend Capital

BAcc; CA (SA); BEE MDP; MBA (Stellenbosch)

Shaun is a director at Transcend Capital, and specialises in BEE Ownership advisory and transaction structuring. Over the last decade Shaun has assisted a diverse range of multinationals and South African corporates build and execute optimal BEE ownership strategy, and has accumulated a wealth of related knowledge and experience. Prior to joining Transcend Capital, Shaun worked for Deloitte and Credit Suisse.

Transcend Capital

Bcom Accounting

Tiisetso is a Director at Transcend Capital. As part of the B-BBEE transaction advisory team, he focuses on the design and implementation of B-BBEE ownership solutions. He has worked on various major multinational deals – providing B-BBEE Ownership advisory, and leading valuations. Prior to joining Transcend Capital, he spent four years in EY’s Transaction Advisory Services team. At EY, he provided buy-side and sell-side transaction, due diligence and valuations advice to multinational corporates and private equity clients.

Transcend Capital

CA(SA), H.Dip Financial Accounting

Snehal is a Director at Transcend Capital. He provides specialist support for the designing and implementation of ownership and enterprise development transactions. Snehal is also a trustee of the Inqolobane Investment Trust. After completing his articles with KPMG, he spent a number of years in the practice as an audit manager. Snehal joined us to pursue his interest in Enterprise Development and the creation of a broader economically active society.

Transcend Capital

BCom Accounting (Hons); CA (SA)

Shelley is the Managing Director at Transcend Corporate Advisors, and, over the past 10 years, has assisted corporates and stakeholders on their transformation journeys. She has advised multinationals, local and listed companies in developing sustainable, high impact BEE strategies. Shelley has developed and integrated Diversity and Inclusion, as well as ESG plans into corporate transformation plans for scalable and efficient impacts. She is passionate about the disability space and manages a team that develops and rolls out accredited training for Persons Living with Disabilities. Previously Shelley worked at Deloitte Consulting and KPMG.

Transcend Corporate Advisors

CA (SA), BCom Accounting (Hons)

Shernon is a Director and Head of Mining Transformation at Transcend Corporate Advisors, and has worked with clients across a number of industries, including multinational corporations to develop sustainable transformation strategies. She has 3 years of experience working at KPMG serving clients with advisory and auditing solutions. She has extensive experience in BEE, Mining Charter and Company’s Act legislation and is experienced in leading BEE audits and the development of integrated transformation strategies.

Transcend Corporate Advisors

LLB (Pretoria), MBA (Stellenbosch)

Neo is a Director at Transcend Corporate Advisors. Neo is a specialist in conducting BEE analyses, identifying transformation opportunities, BEE project management, as well as formulating and implementing sustainable transformation strategies. Neo is passionate about driving real transformation in farming communities, and as such is a specialist in the AgriBEE Codes. Neo also specialises in advising financial services companies under the Financial Services Sector Codes. He has previously worked in legal practice and general consulting.

Transcend Corporate Advisors

PhD, (Demontford), MBA (Wits), BSc Eng (Natal), PR Eng

Robin is a Director at Transcend Corporate Advisors. He is a specialist in corporate strategy development, BEE implementation, and scorecard development. He is a visiting lecturer at the Gordon Institute of Business Science (GIBS) in the fields of strategy development and was previously the director of executive programmes at GIBS. His PhD is in empowerment and he has consulted in organisational empowerment initiatives to a great number of South African and multinational businesses. Robin has written a book on empowerment called Everyone’s Guide to BEE.

Transcend Corporate Advisors

April 15, 2025

March 9, 2025

December 2, 2024